To build a circular economy, make repair the norm

Why changing systems and supporting everyday behaviour is key to lasting circularity

Product repair is one of the simplest ways to reduce resource use and waste, cornerstones of a circular economy. And yet many people still end up replacing instead of fixing. Research fellow Lauren Brumley, part of our environment portfolio, works across several waste and circular economy projects. Here she shares behavioural insights into why this happens, and what can help make repair the easy, obvious choice.

BehaviourWorks Australia: How does repair fit into the bigger picture of a circular economy?

Lauren Brumley: Repair is one of several strategies that seek to retain the value of products for longer. It supports consumers to slow their consumption as through repairing they can keep using products for longer.

And it's particularly relevant in terms of the broader circular economy, which challenges us to think about the whole lifecycle of a product. Repair often starts with designers thinking differently about how products are made and how they can be designed to be repairable. Things like whether products can be easily disassembled with everyday tools.With good product design, the use phase is better supported - meaning the product-user can repair (and maintain) products for longer periods instead of them being disposed of.

Repair can also tie in with other parts of a circular economy. It can enable things like product reuse: a product can be fixed and returned to a really good working state, and then that can be reused by someone else.

Where would you say it has the most impact? Emissions, resource use, or waste reduction?

Lauren: That's a really interesting question, because once again, nothing in a circular economy is simple. For example, there are studies that get into the details of comparing emissions of a new product versus keeping an existing product in life.

But from a household or consumer perspective, one of the most important benefits of repair is waste avoidance.If you can get it working, it doesn’t need to be thrown out. It also helps reduce resource use, because if you are able to continue to use the existing product, you don't need a new one.

In my interviews with the everyday product users, it's often waste avoidance that they're searching for in one sense or another. For some people that is very explicit – they don't want to see an item go to landfill. Others are frustrated about the idea of replacing a product when they haven’t had it for very long or just because a small part of it is broken; for example, disposing of a whole fridge because of a broken button.

What do we know about why people replace rather than repair? Is it systemic – they don't feel they have a choice?

Yes, I think it is systemic. Research I've done with people who have attempted to repair a broken household appliance has highlighted that people can feel as though they're pushing against a system. Interview respondents said that, at each step when they’ve tried to fix something, they felt like replacement was loitering as an easy alternative. For example, they could have a new fridge delivered the next day and the issue would be solved. Others suggested that they felt lonely in their pursuits to fix items, knowing that not everyone would persist.

So I think there is sort of tension between individual agency and structural system barriers. This can include things like not being able to get spare parts, items being out of warranty, and/or no brand or retailer offering repair even if someone wants to be able to.

Broader system barriers exist too. Replacement culture, for example – new products are just a couple of clicks away. And then big-picture norms where 'new' is better. I heard an interesting thing: someone reflected in a workshop earlier this week that most products we encounter are used goods, even if we are the user. If we think about our own goods around the home, they're all used goods to us. But when they break, a lot of people expect a new replacement. I thought it was a good perspective.

Are there any proven interventions that shift people towards repair?

We are about to support a project across one region of Australia to try the effectiveness of a rebate scheme across a range of household products. This strategy has been proven successful in other countries:people are typically offered a partial refund on the repair cost. It addresses several of the financial barriers to having things fixed: the comparison between the replacement cost and the repair cost, as well as diagnostic fees (having to pay a fee to find out if something can be fixed).

Providing information at the point-of-purchase about the repairability and durability of a product is also thought to be effective. For example, the French Repairability Index required several categories of products to display a rating providing consumers with information about how long something lasts (durability) and whether it is likely to be repairable. This kind of intervention is two-fold: it can put pressure on manufacturers to improve their products to achieve a good rating. Plus, by providing consumers with clear information about durability and repairability they can make more informed purchasing decisions.

What are the easiest gateway repairs for consumers? For instance, clothing or small electronics? Is there a simple way to start to get used to the idea of repairing something?

I think fixing clothing is a really easy way to start. Even simple things like mending buttons and small holes are things that are simple to learn. (YouTube is full of great tips!) And there are plenty of alterationists out there who do professional mending. Another way is to make a habit of dropping clothing off to be fixed if taking items to dry cleaners. There are other ways into that, including joining a mending group where they teach darning and have a social element.

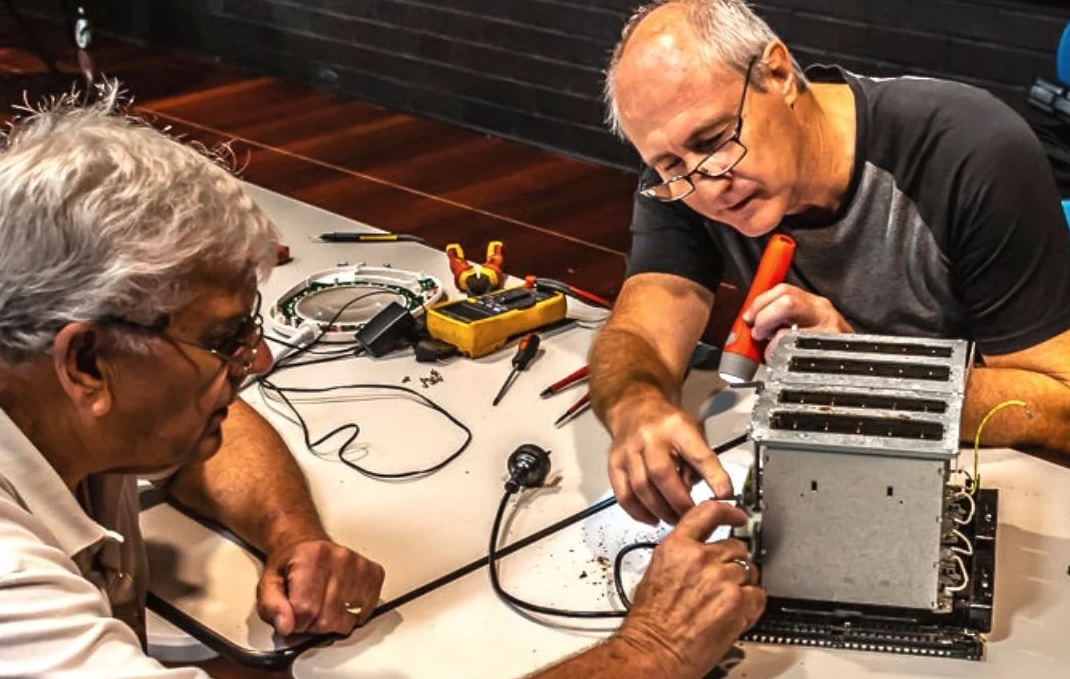

For appliances, it can be good just to make a habit of finding out if an item is fixable by getting in touch with the retailer or brand. And if people are quite interested in how repair works, taking an item to a repair cafe can be a great experience to see how that diagnostic process works. Particularly if you are interested in problem solving.

What about local councils and community groups – how can councils or community groups encourage practical steps? Is it repair cafes?

Repair cafes – yes, increasingly. I've also seen databases by councils, which are quite helpful. As these databases consolidate the commercial and community repairers available in that area across different categories. (See example here.) One of the most challenging first steps for people is knowing where to take something to be repaired. And so these council level databases can be really helpful in that regard.

What promising innovations like tech or business models could make repair the default choice in coming years?

There’s quite a bit of innovation in design for repair and modularity, so that individual components can be easily removed and fixed or replaced as needed, to keep the whole product working.

In terms of business models, this is a really interesting area that we’re just starting to explore. We have a new collaboration between BehaviourWorks, Monash’s Circular Economy Labs, GriffithUniversity and the Product Stewardship Centre of Excellence. This is looking at a whole host of ways to make repair more likely, both by making it easier for consumers to repair, and by making stakeholders other than consumers responsible for securing repair. Some ways that could make it easier include ‘post-in’ options, mobile repair services, or like-for-like loan products during the repair period.

More innovative ideas are product-as-service models, where the retailer is responsible for ensuring you have a working product (e.g. a fridge, washing machine, kettle) at all times – so if it stops working, the retailer has to ensure it gets fixed. And then there are product stewardship innovations, where brands take responsibility for the entire lifecycle of their product and are required or incentivised to make those lifetimes as long as possible.

What about government policy?

Yes, government mandates around manufacturer and retailer responsibility would have a big impact in Australia, having greater regulation on product design standards and warranties. Europe, where there is a more deeply embedded culture of repair, is further ahead in this regard. For example, various regulations are outlining repair and product design requirements that require consumers to be offered repair as an option, making it harder for replacement to be the go-to on warranty claims. That then normalises repair and makes it more likely for out-of-warranty repair by manufacturers also

So here in Australia, greater responsibility by manufacturers and brands could make a big impact because they're often the first place that people go when they have an issue with a product that they think is worth getting working again. If people are told their product is out of warranty and there is no repair option offered, that can be a dead end. There's no responsibility for the manufacturer or retailer to do anything. And there's no information given on what to do next. Now for some people, that's not the end point, but it requires a lot of effort to then go and find another avenue.

Do you have any parting thoughts or words?

I think one particularly important thing to consider in enabling repair, is that it is not only about increasing adoption but considering how to make the process easier. I’ve heard repair stories spanning months - that is a really big commitment for consumers. So any interventions that can lighten the responsibility on consumers to manage the process are worth exploring.