Let's Talk Waste Disposal: A Burning Issue

Bins, batteries and bad behaviours

Small behaviours can have big consequences. Over the past two months, Monash City Council has issued a series of communications around the consequences of the improper disposal of batteries, which have caused fires in two waste collection trucks.

“Early in the morning on Friday 15 August, one of our hard waste collection teams had to dump a load of collected materials in the carpark at Reg Harris Reserve in Oakleigh East because of a fire,” reads one. “Further investigation by our waste team and contractors quickly found that the cause was AA lithium-ion batteries.”

“On the morning of Thursday 11 September, one of our recycling trucks caught fire in Hughesdale. The cause was a rechargeable drill battery wrongly placed in a household recycling bin,” reads another.

According to the council, “any batteries in bins can cause fires in our waste trucks, putting our drivers and waste teams at significant risk and forcing waste and recycling to be dumped in public spaces. Batteries must be taken to a designated disposal point, like a supermarket or Council facility.

Further investigation of the truck's contents by council contractors revealed multiple household electronic items (anything with a plug or cord). Like batteries, electronic items are not permitted in household bins.

We spoke to BehaviourWorks Australia researcher Dr Brea Kunstler on what’s driving these unwanted behaviours, and what might help to turn them around.

When we talk about safe battery disposal, whose behaviour actually needs to change?

Brea Kunstler: Before we try to change a behaviour, we have to identify the behaviour we actually want: who we want to enact that behaviour, and what might get in the way of this happening. This leaves out the unknowns.

In this situation, the behaviour is for people to put batteries in the correct bin. But who are the people? And is it only people, and not organisations, for example, who are responsible for the safe disposal of batteries?

What is the correct bin? Are all batteries accepted? What if the battery is embedded inside an object (e.g. children’s light-up sneakers)?

This isn’t a quick task, but it’s important because it ensures that we’re all on the same page when figuring out what needs to change and how it can be done. Investing time here will help to prevent wasted time and effort later.

What kinds of barriers typically stop people from disposing of batteries safely?

I use batteries in my home, and I have the responsibility of disposing of them. When reflecting on this behaviour for me personally, a few barriers come up:

With two little kids and lots of noisy toys, we use a lot of batteries in our house. Not being able to throw batteries into household waste means I need to have a place to collect batteries that’s away from the kids and that I’ll remember. This is inconvenient and a lot of effort compared to just putting them in the household waste.

These are some barriers I can think of for me, but I’m someone who knows that batteries aren’t meant to go into household waste. For many, not even knowing that batteries can’t go in household waste is a barrier.

Further, these are just barriers for people within the home. What about barriers that exist in the community?

Even for people who do collect old batteries over time, what do they do with a container full of old batteries? People need to put in time and effort to identify where they can take batteries to be disposed of and then take them there. Again, this effort (or “friction”) presents a barrier. Given many people get their groceries delivered now, they would need to find the time to drop off their batteries.

What factors could help make appropriate disposal easier?

Those who are impacted by salient messages and images showing a truck on fire, or rubbish dumped on the street, might be more inclined to put the effort in to collect their batteries and take them to a drop off location. But not everyone is influenced in this way, and so these messages might not be as effective as we’d like. This is especially the case if the message isn’t widely shared or promoted so everyone can see it.

An Australian study conducted in Sydney found that people needing to dispose of their batteries safely would find it helpful to have a deposit return system like that used for bottles, collections at retailers (something that’s happening in Victoria), and having rewards such as new batteries, cash and vouchers. However, incentives and rewards must be sustainable. Sure, providing free batteries might work to get many people to dispose of their batteries appropriately, but who would pay for a program like this, and how long could it be funded for? Also, suddenly removing a reward or incentive for a behaviour rarely sees people continuing to perform that behaviour, particularly if they have no motivation to do so without the incentive.

Once those barriers are understood, how would one design an intervention that actually works in practice?

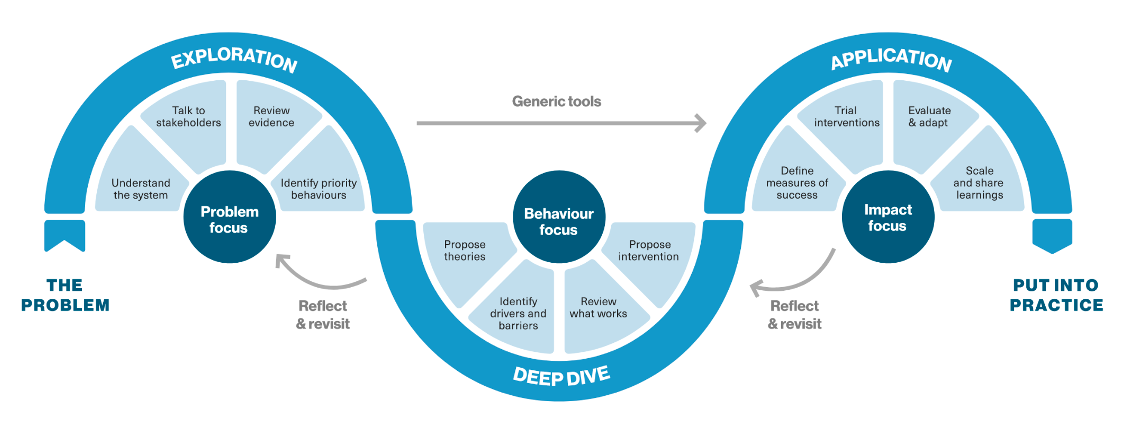

In research at BehaviourWorks Australia, we use what we call The Method to design evidence-based interventions which aim not only to change behaviours but also to have real-world impact. We work together with our partners to understand the behaviour, the drivers and barriers to the behaviour, and the literature that exists to support certain interventions to address the behaviour. Then we design the intervention with our partner before testing it. Although this is an evidence-based framework for changing behaviour, it takes time and skill to implement correctly.

Local councils are often expected to run these kinds of programs — but how realistic is that, given limited resources?

Behaviour change interventions can take time and money to properly design, as outlined earlier. This might not be possible for councils with limited resources. It’s important to use tools and resources they already have, as well as generic behaviour change models, to see the change they need.

If councils can’t invest in a full behaviour change process, what practical tools can they use instead?

Before designing an intervention, it’s important to estimate the number of people and/or groups you are trying to influence. Behaviour change interventions that aim to change the behaviour of a large number of non-specific people (e.g. every household member in Victoria) might have less impact compared to interventions targeting fewer people belonging to more specific groups (e.g. adult household members in the city of Monash). Similarly, interventions designed using a more comprehensive and tailored method (e.g. The Method) compared to a generic method (e.g. EAST, example below) might also see better results. Understanding these limitations will help establish realistic expectations regarding the magnitude of change you can expect to see.

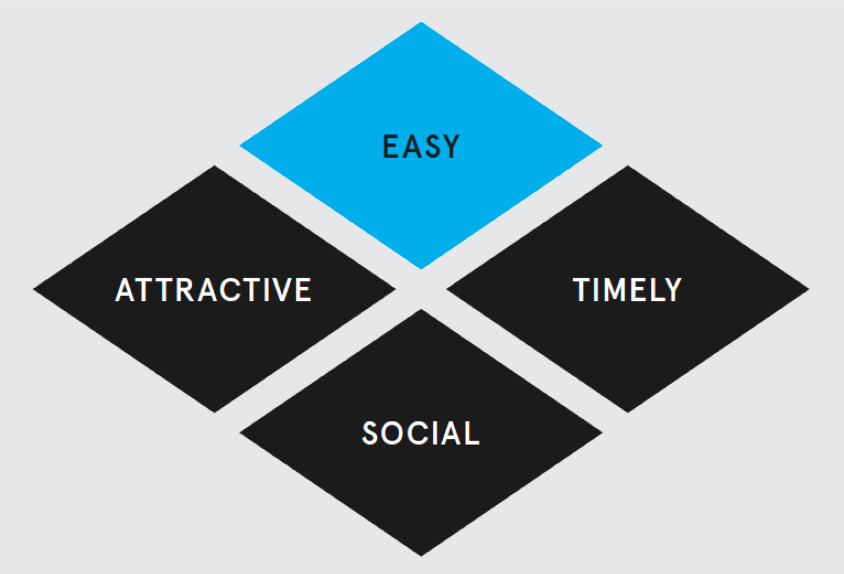

The EAST Framework is a generic behaviour change method designed by the Behavioural Insights Team (BIT) in the UK. It’s a straightforward method and has freely available resources for councils to use to guide their intervention design. It’s evidence-based, built on theory and has been designed for practitioners to apply to their behavioural challenges.

Before using EAST, you need to have a behaviour you want people to perform. Let’s start with three simple questions to design the behaviour and make it specific:

- Who is being asked to change their behaviour? Household members.

- What are they being asked to do? Place batteries in dedicated bins.

- When do they do this?When the batteries need to be disposed of.

This results in the behaviour: Household members place disposable batteries in dedicated battery recycling bins when they need to be disposed of.

What else do you need to know before jumping into helping householders perform this behaviour? Some knowledge of barriers and facilitators could help, as I outlined above. But, how do we know that householders in every local government area experience the same barriers and facilitators? In this case, it would be ideal to speak to local householders to specifically understand their barriers and facilitators to safe battery disposal. However, without time and money to do this, this step is sometimes skipped, and the EAST Framework is applied without this information.

Let’s go through an example of how to use EAST to address the behaviour:

E stands for Easy: How can disposing of batteries in dedicated bins be made easy for householders?

The example from the literature I mentioned above, and an existing practice in Victoria, is to place designated disposal drop-off points in easy to access locations. For me, that’s the library where I take my kids, and the grocery store I shop at.

Although this might sound easy, it might not be easy enough for some. What about for people who don’t go to the library regularly? Or those who get their groceries delivered? Suddenly a strategy to make battery disposal easy isn’t easy at all. Even for those who do regularly frequent the grocery store and library, they still have to collect their batteries at home and remember to bring them with them.

As recent history tells us, this and similar behaviours can be difficult to shift and it takes time (plastic bags at supermarkets being one example). But what we’ve also learnt is that having gone through difficult changes, such as regularly remembering to take reusable bags to the shops with us, can help us to adopt new waste related behaviours through a spillover effect, where performing one behaviour (e.g.taking reusable bags to the shops) makes it more likely that a similar behaviour will also be performed (e.g. safe battery disposal).

A stands for Attractive: How can disposing of batteries in dedicated bins be made attractive to householders?

People love saving money. Even better, people love getting something for free. The study mentioned earlier suggested using incentives and rewards to support battery recycling. One suggestion was giving people new batteries for free when they hand over their old ones. Getting free stuff, even if you need to head to a specific location for the exchange, can be attractive. But is it sustainable?

S stands for Social: How can householders be made aware that disposing batteries in dedicated bins is what other people do, or is what other people think they should do?

Councils often share images of people doing the wrong thing, like a garbage truck fire caused by a battery in household waste. But what if we showed more examples of people doing the right thing instead? When trying to change behaviour, it’s more effective to highlight what we want people to do. Sharing stories or images of relatable locals correctly disposing of batteries at drop-off points helps show what’s normal and socially acceptable.

T stands for Timely: What key opportunities or times exist where householders will be most receptive to messages about disposing of batteries in dedicated bins?

No one wants to see rubbish dumped on the street or a truck driver hurt because a battery caused a fire. While these incidents grab attention, focusing only on what went wrong can reinforce the unwanted behaviour. Instead, they’re a chance to highlight the right action: putting household batteries in dedicated recycling bins. Using these moments to clearly promote safe disposal helps prevent future fires and keeps drivers and communities safe.

For more information on the EAST framework, click here.